Class Notes | 1940's Japanese-American Incarceration

⤏ WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY GISSELLE PERNETT AND EDEN HAIN

⤏ EDITED BY CIANA ALESSI AND FAYE ORLOVE

Class Notes is a recurring series exploring topics that we find hard to understand (purposefully or otherwise!). Started as Instagram infographics, Class Notes has shifted into a monthly Jr Hi the Magazine feature which you can read here!

terms you should know

Executive Order — A signed, written, and published directive from the President of the United States. Executive orders are not legislation and require no approval from Congress. Executive orders remain in place until a sitting United States President overturns it. Only a sitting U.S. President may overturn an existing executive order by issuing another executive order to that effect.

Fifth Column — Refers to a large group of people who undermine the current mainstream ideas of the time. Often used to refer to a group of people who plan to topple a government through clandestine means, espionage, or sabotage. During the 1940’s, Japanese-Americans were referred to as the Fifth Column to further heighten racist paranoia.

Internment — Mass imprisonment of a people during wartimes with no charges filed.

Issei — First generation Japanese. Born in Japan and migrated to another country.

Nisei — Second generation Japanese-Americans, born to Issei.

JACL — The Japanese American Citizens League. Hoped to prove their loyalty to the United States government by entering internment with minimal opposition.

Martial Law — Invoked in times of war or rebellion. When in effect, the military commander of an area has unlimited authority to make and enforce laws.

Reparations — Compensation for egregious wrongdoing through monetary or similarly financially equivalent means.

War Relocation Authority (WRA) — A federal agency created in 1942 in response to the signing of Executive Order 9066. The WRA was responsible for segregating Japanese-American people from coastal cities and resettling them into war relocation camps. The WRA were terminated by Executive Order 9742, signed by Harry S. Truman in 1946.

Xenophobia — Prejudice. Fear or hatred of that which is foreign or of another country.

Yellow Peril — Racism against Asian people — specifically those who immigrated to the United States — out of fear of displacement in their country and disruption of Western values.

AMERICAN XENOPHOBIA

Our reason for choosing this topic is, well, this series is written by two Californians — born and raised — who were never formally taught about Japanese “internment.” Internment in quotes because, while the actions of the United States government falls under the definition of internment (see glossary above), the years spent in these War Relocation Centers is far more akin to incarceration. And wrongful incarceration at that. Moving forward, it’s important to note the language that was used at the time, but now update the terminology in accordance with revisions made by Japanese-Americans and scholars of the era. Instead of “internment,” we say “incarceration,” “internees” as “incarcerees.”

“Since the 1970s, Japanese Americans, historians, educators, journalists, and others have increasingly advocated for the use of terminology that more accurately represents this history. Rather than repeat the euphemisms used by the U.S. government and other defenders of WWII incarceration, we encourage individuals to think critically about the impact of words like “internment,” “relocation,” and “evacuation.”

In the words of…Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, “words can lie or clarify.” [2] When we use language that distorts the past, we lose our ability to recognize patterns of repeating history. But language that imparts truth and understanding can help us avoid repeating those same mistakes today.” — Densho, The Japanese American Legacy Project

As much as we thought we knew about this state we call home, much of this information is new to us. And so much of it has been buried by America’s general mission to suppress history and the Californian emphasis on a melting pot culture. …As if.

America’s xenophobia towards the Japanese didn’t just start as a reaction to World War II; fear of Japanese people and Japanese immigration had been plaguing our lawmakers as early as the 1910s when the first limits on — specifically male — immigration were passed.

In October 1941, investigator Curtis Munson was hired by the Roosevelt Administration to look into the inner workings of Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast. The idea of establishing American concentration camps was considered, because American presidents famously love methodically collecting and killing minority populations, but instead, Munson first worked with the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence to interview Japanese-Americans. Ultimately, he concluded his reports by saying,

“We do not want to throw a lot of American citizens into a concentration camp of course, and especially as the almost unanimous verdict is that in case of war they will be quiet, very quiet.”

John Franklin Carter, a renowned journalist, passed on this message to President Roosevelt:

"The essence of what [Munson] has to report is that, to date, he has found no evidence which would indicate that there is danger of widespread anti-American activities among [Japanese-Americans]. He feels that the Japanese are more in danger from the whites than the other way around."

Then, on December 7, 1941, the Hawai’ian naval port Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan, resulting in a high American death toll. The months following Pearl Harbor were filled with congressional committee hearings trying to subvert another surprise attack. Naturally, America shifted their focus to “preventing Japanese espionage” AKA validating their paranoia and racism.

mass INCARCERATION

February 19, 1942 — President Roosevelt signed EO 9066. EO 9066 commands the United States to be tough on espionage. It declares anyone accused of spying against America can be removed from their home and thrown into internment accommodations for the duration of the war. Originally the executive order laid out a plan to detain Japanese Americans on a voluntary basis. Obviously this is a great idea. Personally, as a spy, I turn myself in all the time.

March 21, 1942 — When people weren’t leaving their homes to enter voluntary incarceration, Congress passed Public Law 503. A $5,000 fine was enforced on all people — but only of Japanese descent — who violated Executive Order 9066.

March 29, 1942 — Public Proclamation No. 4 decreed a 48 hour notice for Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans to vacate their homes and check into war-time accommodations. If you’re thinking this sounds like “throw a bunch of families into horse stalls for 3 years,” you’d be correct!

war relocation centers

In the continental U.S., the WRA herded Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast into “War Relocation Centers” — temporary holding places for the temporary holding places they would be moved into for the duration of the war. Yes, you read that right. Now, if you live in Los Angeles, you may have been to Santa Anita Park for a concert on a summer night, or placed bets on jockeys during the day. Or, if you were a Girl Scout in the early 2000s, you may have gone to a career fair and learned about cookie-based entrepreneurship. Just me? Cool. Well, not even ten years after it opened, Santa Anita Park was also the site of one of the largest War Relocation Centers. Yes, Japanese-Americans were sleeping on sacks stuffed with hay, in horse stalls, sharing space with multiple other “interred” families. The U.S. essentially said, “You can’t live in your house while we build your prison, that would be too humane. Instead, you have to live in a horse stall while we build your prison.”

The powers that be did consider mass incarceration in Hawai’i, however, there were too many Japanese-American people to “inter.” Mass interment would, therefore, have created an economic crisis by imprisoning the cheap-labor-pool, so the government decided: MONEY FIRST! MARTIAL LAW! STRIKE FEAR, BABY! And no, you cannot have any civil liberties.

On December 7th, Martial Law was declared in Hawai’i. Japanese-American residents in Hawai’i — mainly influential leaders, teachers, and priests — were detained immediately. Those detained were held at detention facilities, immigration stations, and police departments before being transferred to Sand Island Incarceration Camp. Incarcerees at Sand Island were treated as prisoners of war, forced to sleep on cots and stripped of their belongings. Over 450 residents — primarily men — were held at Sand Island before the camp closed in March 1943. Incarcerees were then moved to the Honouliuli Incarceration Camp on the mainland. Honouliuli, referred as “hell valley” due to the extremely hot and humid climate, became Hawaii’s largest War Relocation Center. In the following months, the horrors progressed:

June 1942 — The film “Little Tokyo, U.S.A.”, produced by Twentieth Century Fox, was released. It was point blank fear mongering propaganda to further perpetuate Yellow Peril.

June 17, 1942 — After 90 days as head of the War Relocation Authority, Milton Eisenhower resigned, seeing the camps as an unjust confinement of innocent people. He was replaced by Dillon S. Myer, who ran the WRA until the dissolution of EO 9066.

August - September 1942 — Japanese people are moved from temporary holdings in racetracks around the country into “Internment camps.”

incarcerated life

Incarcerated life varied from state to state. Often compared to German concentration camps, incarcerees were similarly under 24/7 armed surveillance, however, the incarcerated Japanese-Americans had relative freedom. Of course they couldn’t leave of their own free will, and they couldn’t even walk too close to the barbed fences without coming under fire, but they were able to create a semblance of civilized life. While the incarcerated peoples did not have to work, they could make some money while they were forced out of their homes. SOME being the operative word. The amount of money incarcerees made as doctors, teachers, or manufacturers of goods used in other prisons or by soldiers fighting in the war could not exceed an Army Private’s salary: approximately $50/month, or in today’s money, $676.51. This wouldn’t even cover half of my half of rent.

And while accommodations varied from place to place, they all had to abide by wartime rationing. Each community had the added complication of trying to appeal to two generations of wildly different palettes. Issei craved Japanese staples like fish and rice while Nisei missed the American food they’d been raised eating. For months, the incarcerees fought for rice to be added to their meals. The American government was so clueless, they provided the camps with potatoes and macaroni. Frankly, all that mattered was that each person was fed for less than 50 cents a day.

In trying to make food that tasted marginally okay and could be eaten across the generational divide, the incarcerated Japanese-Americans got used to the cheap sausages and fruit served with their rice. Some of the meals that were developed out of necessity are still eaten today, in much more comfortable conditions, or hawked out of duffel bags at the back of third period chemistry class by students who need extra cash for gas. That’s everyone’s first experience with Spam Musubi, right? Or Weenie Royale (aka fried rice with hot dogs)? Now a camping trip mainstay, these meals were results of all the protein and starch the U.S. military budgeted for incarcerees’ daily meals.

“[The incarcerated Japanese population] established newspapers, markets, schools, and even police and fire departments. At the Rohwer War Relocation Center in southeastern Arkansas, Japanese American high school students had their own band, sports teams, clubs, and activities like senior prom and student council. Flipping through the pages of the school’s yearbook, however, the makeshift barracks of wood and tar paper, the guard towers, and the barbed-wire fences visible in the photos are an obvious reminder that the experiences of these students were anything but normal.” — National world war ii Museum of new orleans

![Tojo Miatake [i.e. Tōyō Miyatake] Family, Manzanar Relocation Center](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56eadb72d51cd4a1f93f5e10/1653416106529-6MQ4ZRK2FHWQ1EMP3PSP/download1.png)

All photos by Ansel Adams

loyalty questionnaire

After a year of keeping Japanese-Americans imprisoned, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority created the “Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry” AKA the “loyalty questionnaire.” The purpose of the loyalty questionnaire was used to determine which incarcerees were “disloyal” and which were “loyal” enough. Enough for what? Sometimes to be released into regular society (as long as they didn’t go to the West Coast). Sometimes to be considered to remain in the same “accommodations” they’d been living in for the last 2 years. Sometimes to fight in the war for the country that’s imprisoning them. Not sure how sharing my hobbies and providing the names of magazines I read will determine if I’m loyal to the U.S., but sure! (Yes, these were real questions on the questionnaire.)

Questions 27 and 28 were considered the most controversial questions on the form. Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, whenever ordered?” Question 28 asked, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?” These questions caused confusion amongst the incarcerated population. Notably, because there are way too many clauses in Question 28. We are native English-speaking Americans, taught under the iron hooves of the American public school system, and still had to re-read that question at least three times.

But more importantly, because a month after Pearl Harbor, the War Department categorized Japanese-Americans as “enemy aliens” and banned them from enlisting in the military. Those in the camps, therefore, wondered if responding “yes” to question 27 meant they were volunteering to serve the same country that was denying them basic human rights. Question 28 confused Issei incarcerees because they were being asked to swear allegiance to the country that had denied them citizenship, while Nisei were angry because they were being asked to denounce an emperor they were never loyal to and swear their allegiance to the country that kept them imprisoned.

Some incarcerees used the loyalty questionnaire as a form of protest. Not answering the loyalty questionnaire, or answering “no” to question 27 or 28, resulted in forced removal from their current incarceration accommodations and moved to Tule Lake, the largest of the relocation camps. Because it held so many “disloyal” incarcerees, Tule Lake was converted to a high security segregation camp.

On November 1, 1943, The Daihyo Sha Kai — a negotiating committee formed by incarcerees at Tule Lake — met with directors of the WRA to explain their outrage over the unsanitary living conditions, unsafe work environment, and lack of food and medical care. Between 5,000 and 10,000 of the people incarcerated at Tule Lake showed up to the administration center to peacefully support their committee leaders. If you thought the WRA directors would listen to these very valid complaints, you would be wrong! So very wrong. The WRA directors basically said, “cope.” When an outpouring of Japanese-Americans showed up in peaceful solidarity, the WRA staff did what white people do best: built a wall!

Following this failed negotiation, Tule Lake was occupied by the army and placed under Martial Law, resulting in curfews and a complete stop of all activities. Daihyo Sha Kai leaders and other influential protesters were imprisoned in yet another prison since they were seen as too educated and were accused of troublemaking.

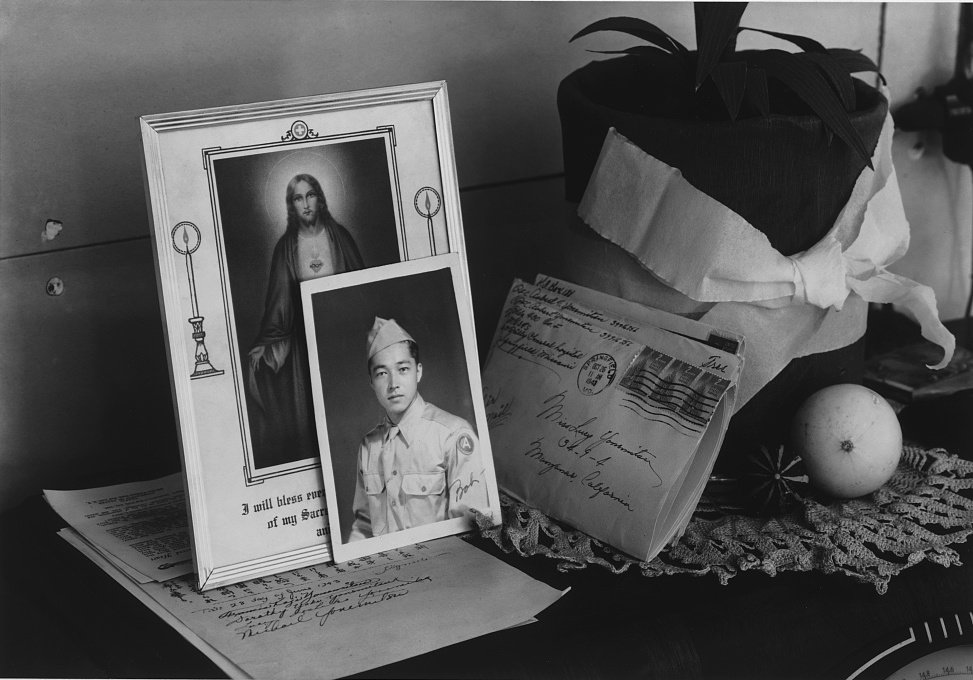

Using the loyalty questionnaire, the military planned on recruiting 3,500 Japanese-American men from the incarceration camps to form a segregated combat team. Only 1,238 men volunteered, hoping they could gain some of their rights back and attempt to prove their loyalty to the U.S. As it turns out, not many would choose to defend the country that kept them forcefully imprisoned. Strange, right? The military drafted 4,000 Japanese-American men to form the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, with most of the 442nd Regiment’s soldiers being Japanese-Americans from Hawai’i.

Following the unexpected draft resistance, President Roosevelt signed Public Law 405 AKA the Renunciation Act of 1944. This meant “serve the country that forced you out of your home… or get outta here!” Some Issei believed they would be better off moving back to Japan and resettling after the war. In an effort to remain with their Issei family members, some Nisei renounced their citizenship and were sent to Japan. Others renounced because they couldn’t picture a future in the country that kept them wrongfully incarcerated. Between 1944 and 1945, 5,589 Nisei renounced their citizenship, most of them from Tule Lake.

REINTEGRATION

December 1944 — President Roosevelt unofficially ended EO 9066 a day before the ruling for the Supreme Court case — Ex Parte Endo — was issued. In 1942, Mitsuye Endo, an American DMV employee of Japanese descent, was fired from her job and moved to an incarceration camp. Attorney James Purcell used Endo as a test case to file a writ of habeas corpus because she represented an assimilated and loyal Japanese-American. The petition was denied, but in an attempt to stop Endo from appealing, the government offered her release from the incarceration camp, with the condition that she could not return to the West Coast. Endo refused and remained in the camp until her petition was reviewed by the Supreme Court in 1944. The Supreme Court ruled the government could not confine citizens who were loyal to the U.S.

January 1945 — The war relocation centers officially closed. The last to close was Tule Lake in 1946.

February 1976 — Proclamation no. 4417, signed by President Ford, officially terminates EO 9066.

July 1980 — The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was created to review the facts about EO 9066 because the blatant xenophobia obviously wasn’t enough. The report was published in a book called, Public Justice Denied, and concluded that, “Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity but rather was the result of "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership."“ This led to the creation of the Civil Liberties Act in 1988.

The first reintegration efforts began as early as December 1942 when Issei lobbied for the education of university-aged incarcerees to be prioritized. Approximately 800 Nisei accepted into universities (again, as long as it wasn’t on the West Coast) were granted leave. In 1943, farmers could apply for temporary leave to labor in neighboring fields. They made far less money than they had before they were incarcerated — and were granted minimal protections from the racism that surrounded them — but accepted the break from life in the dusty camps.

Even those who proved themselves loyal to the U.S. government were understandably wary to resettle outside of the camps. For thousands of incarcerees, leaving the concentration camps meant re-entering society with less job opportunity, restrictive covenants in the housing market, and intense poverty. Many were afraid of the racist attacks they would face in their new lives on the outside, and others were just ambivalent to start again because there was nothing to return to.

Throughout WWII, only ten people were convicted for spying for Japan. All of them were white.

Many Sansei (third generation Japanese-Americans, born to Nisei) encouraged still-living Issei and Nissei to speak out about their traumatic experiences living in confinement or testified on the impact on their families. Over 750 incarcerees spoke out in 20 West Coast cities in a movement supported by both local and national groups like the Japanese American Citizens League and Nikkei for Civils Rights and Redress (formerly known as the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations) to tell their own narratives. This grassroots effort to ensure that survivors voices were heard led to President Reagan into signing The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, compensating over 82,000 surviving “internees” with a public apology and tax free checks worth $20,000 (around $39,000 in today’s money.)

We would like to reiterate the fact that most — if not all — of this information was not taught to us when learning about World War II. Shout out to the white American education system and the continued deliberate erasure of obvious racism! Today, most of these “internment camps” have been preserved as historic sites and monuments. Diving deeper and actually learning about these concentration camps has caused us to think about all the ways American history is riddled with trapping the people of this land into cages. It’s hard not to compare the WRA to the California Missions. It’s hard not to compare the WRA to ICE. Accusing people of “not being American enough” is almost more American than apple pie. But we continue to free ourselves not by imprisoning others, but by sharing our histories and not allowing them to be forgotten.

SOURCES AND ADDITIONAL READING

Japanese Internment by History.com Editors on History.com

Japanese-American Incarceration During World War II from the National Archives

Why the US photographed its own WWII concentration camps from Vox Editors

Japanese American Incarceration from the WWII Museum of New Orleans

Families, Food, and Dining from the National Parks Service

Weenie Royale: Food and the Japanese Internment produced by The Kitchen Sisters

Food of the Incarcerated: Internment & Resistance by Freedom Nguyen

Food from the University Libraries of the University of Washington

Terminology from Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project

Children of the Camps from PBS

Japanese-American Internment from the Harry S. Truman Library & Museum

Information on Tule Lake provided by the Tule Lake Committee

Additional thanks to Joy Yamaguchi for their guidance and edits on this whole piece, and the Japanese American National Museum for allowing us to visit their location and learn from their collections.